23 Mar March 22, 2023: Day 4

Hatzeva Field School

We drove through rows of organic pepper and tomato greenhouses as Dorit introduced us to her home, the Hatzeva moshav. Solar panels lined the roof of facilities near the entrance of the moshav, and palm trees stretched towards the sky along the horizon. We drove down a road called the Peace Road, and saw Jordan in the distance. Jay Shofet, SPNI’s Director of Development, explained that we don’t see water in the Arava stream nearby because it doesn’t constantly flow here. “You can tell where the floodplain is though, because of the line of vegetation,” he noted.

Miki, a teacher at the Hatzeva Field School, said she teaches her students about the conflicts in the desert around agriculture and development. “You can see what the environment is going to do for animals, agriculture, and people,” Miki said. Despite the potential, when people first came to this area, the government thought it was impossible to live in the desert. Additionally, this was a very risky area before peace was made with Jordan, Reut told us. Just like nature, though, the people here have adapted to the harsh conditions of the desert, and thrive here against the odds.

We arrived to the most arid landscape we have seen on the trip thus far, with only sand and a few spiky trees in view. Reut told me that the crown of thorns that Jesus wore when he was crucified were allegedly made out of these types of trees. Guiding us through the desert was Oded Keynan, an expert in animal behavior and desert ecology. Oded whistled one or two long notes as he led the group, calling out to the birds he had built relationships with in their language.

Finally, we saw them: Arabian Babblers. We sat in the sand and the birds came right up to us as Oded threw them Cheerios. He explained the rings on the birds’ legs and how they identified each of them by name. We were introduced to Atul, the 13 year old dominant female of the group. “Only the dominant male and female reproduce, and the rest of the birds in the group help them raise their young,” Oded told us.

We saw a continuation of this bird benevolence when one babbler landed atop the tree to guard the rest of the group. “guarding the group gives up his chance to eat and he now has a bigger chance to be attacked by a predator,” Oded translated. Once the birds finished eating, they flew into the tree and began preening each other. “This is a bonding moment like hugging, and removes stress,” Oded said,

“We see individuals taking care of each other, taking care of the group. How does this work in evolution? Why stay in the group?”

Oded revealed there were multiple theories to answer these questions. “When the cost of living outside is hard, we live with our parents,” he noted, “and these babblers need to cope with the harsh conditions of the desert.” There are about 20 groups of babblers that Oded studies here, and they are all very curious and friendly.

Oded told us about the different warning calls that the babblers have for different predators, and how their calls change in urgency based on the various proximities of said predators. Walking a bit, we learned about the wolves in the area and their experiences in Israel and Jordan. “Sadly, the animals that cross the border for Jordan often get shot,” Oded explained, “the wolves have a really interesting dissonance where they can drink from streams and have free rein in Israel, and then when they cross the border they are shot at and endangered.”

We were soon acquainted with a large Acacia tree. We learned about its relationship with the other plants and animals in the desert, and how it maintains a mutually beneficial partnership with many of them. This beautiful tree was an encouraging illustration of how interconnected everything in a habitat is, and especially how we, as humans, could behave with regard to the world around us.

Kibbutz Ketura

Eliza Mayo greeted us at Kibbutz Ketura, and we were offered coffee and tea on a refreshing patio space. Students in the area were visiting with each other, and two beautiful swings enticed a few of us.

“The environment knows no borders.”

Eliza commenced with this revolutionary statement, “and neither do our resources. Our mission here is trans-boundary management of these resources.” She explained the academic program taking place at Kibbutz Ketura, and how it brings together students from Israel, Jordan, Palestine, and other countries to live together, study the environment, and take part in structured dialogue forums about history, politics, culture, and other topics.

We toured the site, and saw three structures that were designed to stay cool in warm environments, have good air circulation, and utilize inexpensive materials for construction. All three had solar panels on the roof, and provided solutions for rural, suburban, and urban homes.

We also got to see a bio-digester, a big black bag with a funnel attached that transforms waste into energy and fertilizer, in a completely odorless process. People can dispose of their organic waste into the funnel, and bacteria that lives in the bag then transforms it into a biogas that is used to fuel a stovetop, and liquid fertilizer that can be used to nourish crops.

All of these alternative energy sources and spaces at Kibbutz Ketura act as inspiration, foundation for further research, and applicable findings for any community. From the cross-border teamwork to the advanced innovation, touring this kibbutz was an extremely valuable experience.

Timna Park

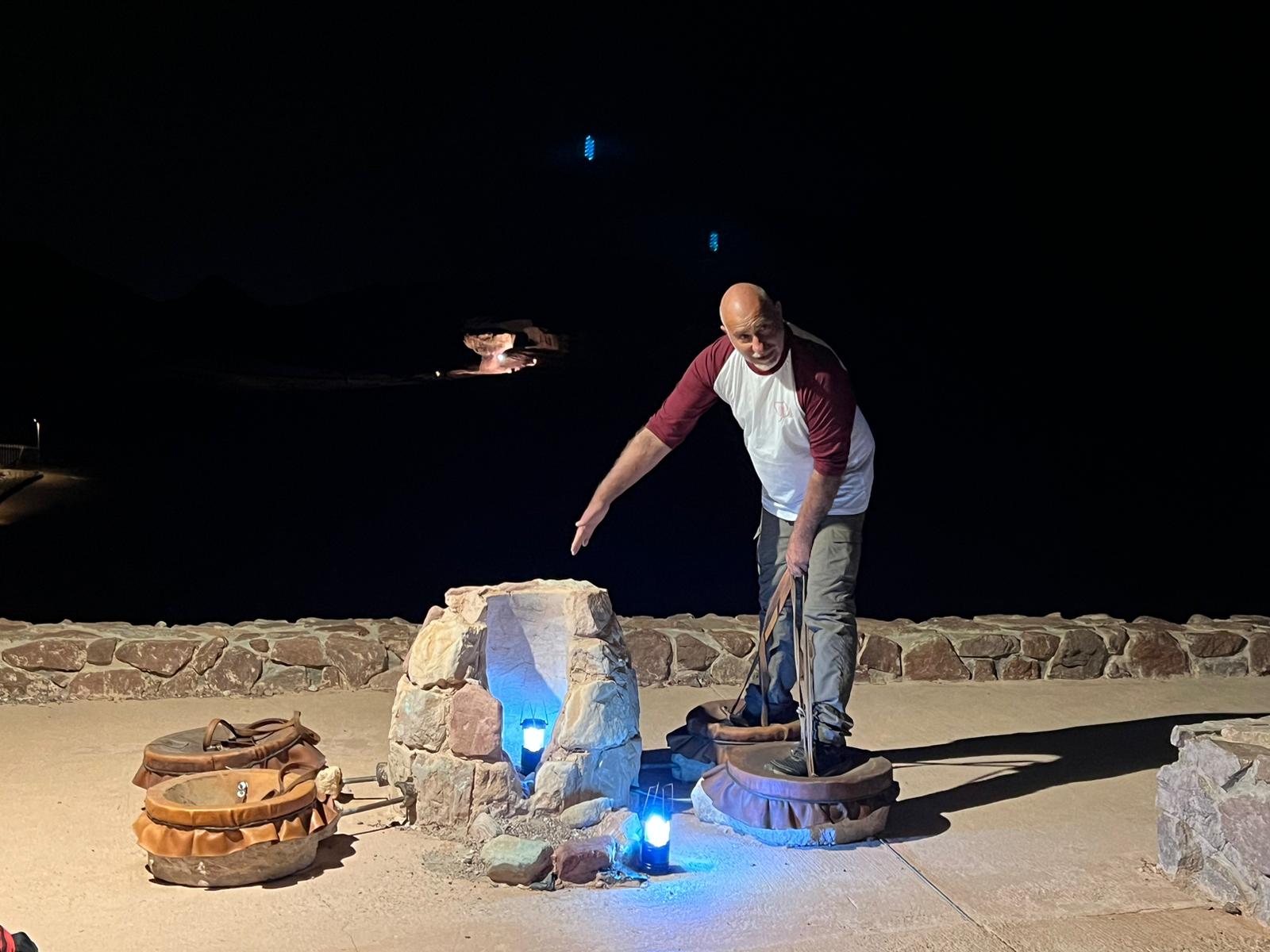

“A gerbil just crossed the road,” Limor, our guide for Timna Park, informed us as we drove through the desert at 8pm. In the distance, we saw the Mushroom, a huge mushroom shaped rock formation illuminated against the dark, starry sky. Limor explained the history of this site, and its significance in the Egyptian period. “Pharaohs used to have people here to look for copper,” he said, “not slaves, but local workers.” Using the furnace and billows as props, Limor demonstrated, “The workers used to break the rocks into little pieces, and then they would put the crushed stones into the furnace. The result was copper and slug byproducts.”

How amazing that thousands of years ago, a mineral was harvested here that is used today in the production of computers, allowing Amir to share the data he collects on migrating birds, Evyatar to print informational panels to educate field school students, and you to be reading this blog right now.

We walked over to the Mushroom, led only by Limor and the lights of our lanterns. The red sand, rich with copper and other minerals, glistened under our feet. The Mushroom was massive up close; participant Daphne White later told me that when she was confronted with the immensity of this uniquely shaped eroded sandstone, she was overwhelmed by a sense of cosmic insignificance, reminded of how little she is in the vastness of nature.

We visited Solomon’s Pillars soon after, and were impressed by the dramatic sandstone formations making up the wall of the cliff. Limor told us that the architectural research of Professor Erez Ben-Yosef proved that King Solomon and King David’s period was much more significant and active in Timna than the Egyptian period. For this reason, these pillars were named after the renowned biblical monarch King Solomon.

The scenic treasures of Timna have beautiful national trails that run through it, and SPNI is responsible for marking and blazing these trails. The abundance of accessibility SPNI designs and implements for these sites, and the upkeep and protection of them is incredible, and I felt extremely proud of my personal support of such an intelligent and altruistic organization.