06 Nov November 5, 2025: Day 4

by Jessica Lewis, Director of Marketing and Communications at Nature Israel

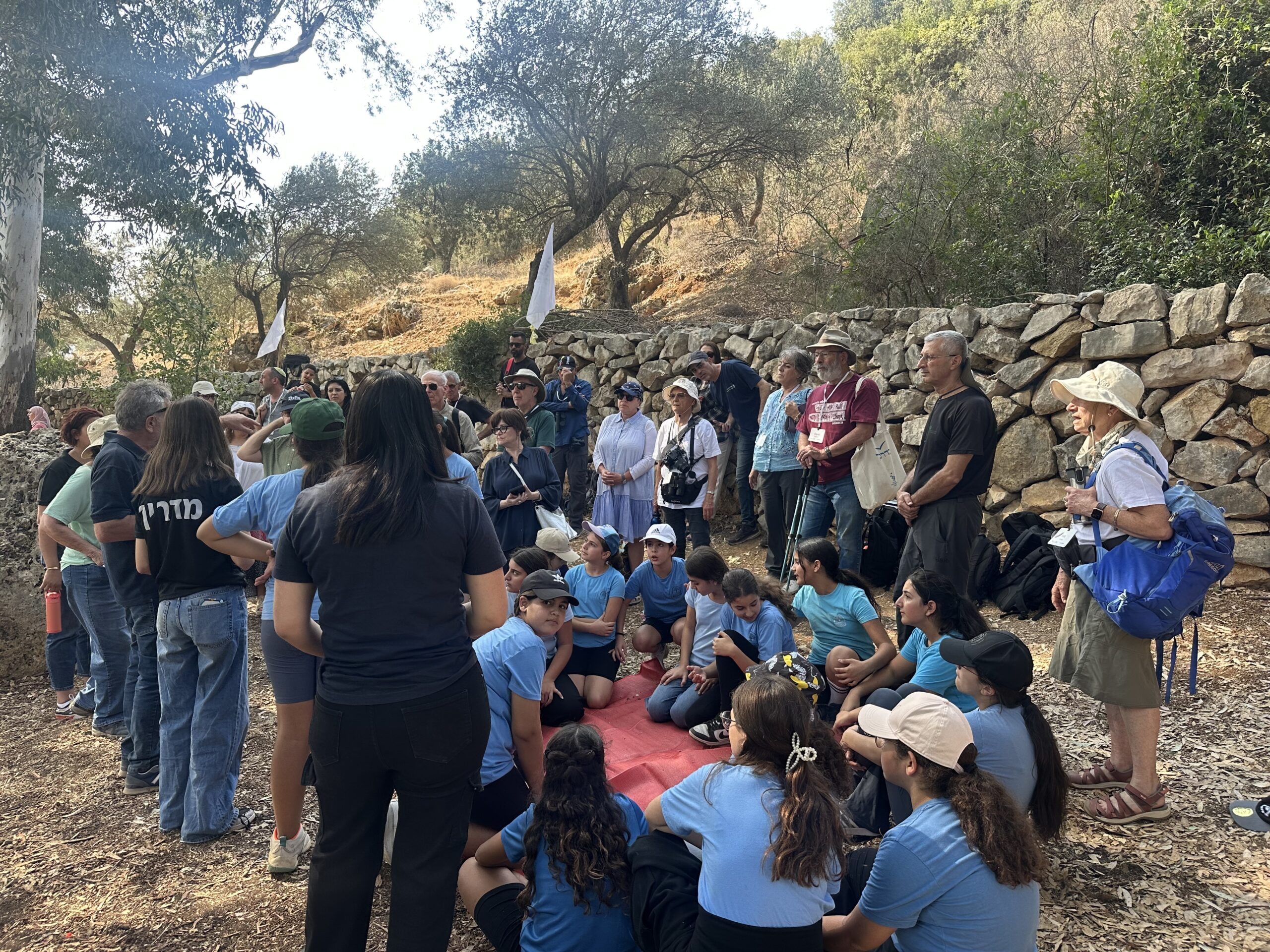

Activity with Israeli-Arab Students

In the Galilee, we joined a group of Arab Israeli students for outdoor learning. Arab citizens make up about 20% of Israel, and nearly 80% of the population in this region, so SPNI’s nature education work here is not peripheral, but central. Their teams work across the country, from preschool through high school, training teachers, partnering with local councils and mayors, and building programs in Hebrew, Arabic, and beyond. They even work with the waqf in East Jerusalem. “We work system-wide,” one staff member explained, “from north to south, from preschool to high school.”

The students we met were from the village of Ramah. They were doing something called “postal nature,” a sort of outdoor scavenger hunt. Each group received a different task: find five things of the same color; find three things that will still be here fifty years from now. The goal was simple, explore nature. Notice what lives here with you. When groups returned, one educator guided them deeper: What did you find? Who depends on it? What responsibility do we have toward it?

“The idea is to open your eyes. To know the plants and animals. To understand you belong to this place — and it belongs to you.”

As Rachel reminded us, Israelis grow up knowing what birds live around them, where the spring begins, and what wildflowers bloom nearby, a culture shaped by decades of SPNI programs; Even the iconic wildflower campaign — a public education and legal initiative launched by SPNI in 1964 to prevent native wildflowers from going extinct due to widespread picking — is now second nature.

The students we met were from the nearby village of Ramah, and it was clear how much our visit meant; they wanted photo after photo, proud to show that Americans cared about what they were learning. Being seen mattered, it affirmed that their connection to nature is valued. Lawrence noted that this isn’t a program imposed from the outside, but one in which “people in the local community [are] educating their own people.” Trip participant Iva said it beautifully:

“The big idea was hope — hope for a beautiful future for our world, for nature, for all of us together.”

Near the trail, a small sign pointed out that the stream is habitat for an endangered salamander, a reminder that the curiosity and care these students are building is helping protect the species that live alongside them.

Lunch in a Druze Home

We were welcomed into the home of a Druze family whose roots in this region go back more than 400 years. Three generations live within steps of one another, our host in one house, his parents just across the courtyard, and his uncles next door. He shared that while in the U.S. a town made up mostly of one ethnicity might feel unusual, here it reflects a long-standing, traditional way of life. The Druze, he explained, “don’t believe there should be borders, just one world, planet Earth.” Because every place is equally holy, they can pray anywhere, at home, in nature, wherever they happen to be. And of course, the food was incredible — warm grape leaves, chickpea stew, and cold tamarind juice that tasted both familiar and entirely new.

When asked about the relationship between the Druze and nature, he answered simply: “we aren’t separate from nature; we are integral to it. Like a flower that grows and returns to the earth, people do too.” He spoke with quiet pride about how the Druze have protected and supported Jewish communities since the late 1800s, and how they raise their children with a strong sense of belonging to the land. When a baby is born, families say:

“Anachnu haTeva, this is your country, and it belongs to you. This is your tree, and you must protect it.”

Maagan Michael Rewilded Wetlands & Birding Park

Our last stop of the day was Maagan Michael, where the sun was beginning to soften over the wetlands. As we stepped out, trip participant Naomi smiled and told me, “I stayed here in 1976,” a small reminder of how long people have been connected to this landscape. We were joined again by Yoav Perlman, who explained that SPNI’s approach here is rooted in community partnership:

“We always work with the local communities. We work in full partnership with the kibbutzim and other organizations.”

That spirit of collaboration is part of what has made rewilding possible, turning old fishponds into thriving wetland habitats for birds and other wildlife. Dan Alon reflected on how community attitudes have evolved: years ago, locals weren’t interested in eco-tourism; Now, the same community is asking when the next rewilding project will be. As one kibbutz member told him, protecting nature has changed daily life here; the beauty of the wetlands is so wonderful for the people who live alongside them, and if tourists enjoy it too, all the better.

Through a shared scope set up near the water’s edge, we could watch these birds closely enough to see the small ripples around their legs, a beautiful reflection that restoring nature includes people, too.

As the sun dropped, pelicans drifted across gold-washed water. Jonathan Silverstein, SPNI’s board chair, who has watched this project grow from its earliest days, noted that even the most celebrated outcomes weren’t what anyone initially imagined. Looking out over the water, he said, “I don’t know that was part of the initial benefit,” referring to how rewilding not only restores habitat but also creates spaces where people can sit, observe, and feel connected. But that’s the beauty:

When you start protecting nature, all kinds of good follows.

Dan poke of SPNI’s next goal: rewilding the vast Kabara Marsh, nearly 200 times larger than the wetland before us. Lawrence added, “That’s how NGOs work, to do something everyone thinks is impossible, and then everyone wants a piece once it works.”