18 Jul Adventures from SPNI, Intern Edition 2

By Luke Finkelstein

We were already on the road. It was 4:30 am, and the world out the window was dark and still. Few people were crazy enough to wake up that early for a birding adventure. I had expected that a 3:30 am wake-up would have been sufficiently early, and it was like my traveling companion could sense what I was thinking, for he said, “Usually I’d go earlier, at dawn. That’s the ideal.” I gulped. Hints of dawn were sneaking up the sky, and we wouldn’t arrive to Kfar Ruppin, the kibbutz and birding site, until sunrise. Had the wake-up been in vain? My tired body shrunk from hearing it.

“But this is the second most ideal time, right?” I asked hopefully.

He laughed. He grinned a little, despite the tiredness.

“Yes.”

I had been speaking to Dr. Yoav Perlman, the director of BirdLife Israel. BirdLife Israel is a branch of SPNI that focuses on conservation of the birds of Israel and their habitats. Birder, ecologist, conservationist, wildlife photographer, and expert out-of-doors coffee maker, he was now adding to his impressive list of talents travel companion to two SPNI interns—me and Adin. In fact, the reason we were heading to Kfar Ruppin at the second most ideal time, rather than the first, was because Yoav had had to pick up both me and Adin at our separate locations in Tel Aviv. Few buses ran at that hour, and Adin and I lived on opposite sides of town. Now, hands gripped on the wheel and eyes drawn into alertness, Yoav drove with an air of determination. Despite his reassurance, despite his smile, he leaned forward in his seat, as if to say, “birds, wait up! We’re coming.”

Kfar Ruppin is a remote kibbutz south of the Sea of Galilee pressed tight against Jordan, about an hour-and-a-half-long drive from Tel-Aviv. When we arrived on site, the sun had already begun to peak over the horizon. The sun rose quickly here; it shot out of the hills on the Jordan border and never stopped, its young warm rays signaling the heat to come. Yoav, Adin, and I stepped out of the car into the stirring sounds of life. The birds had waited.

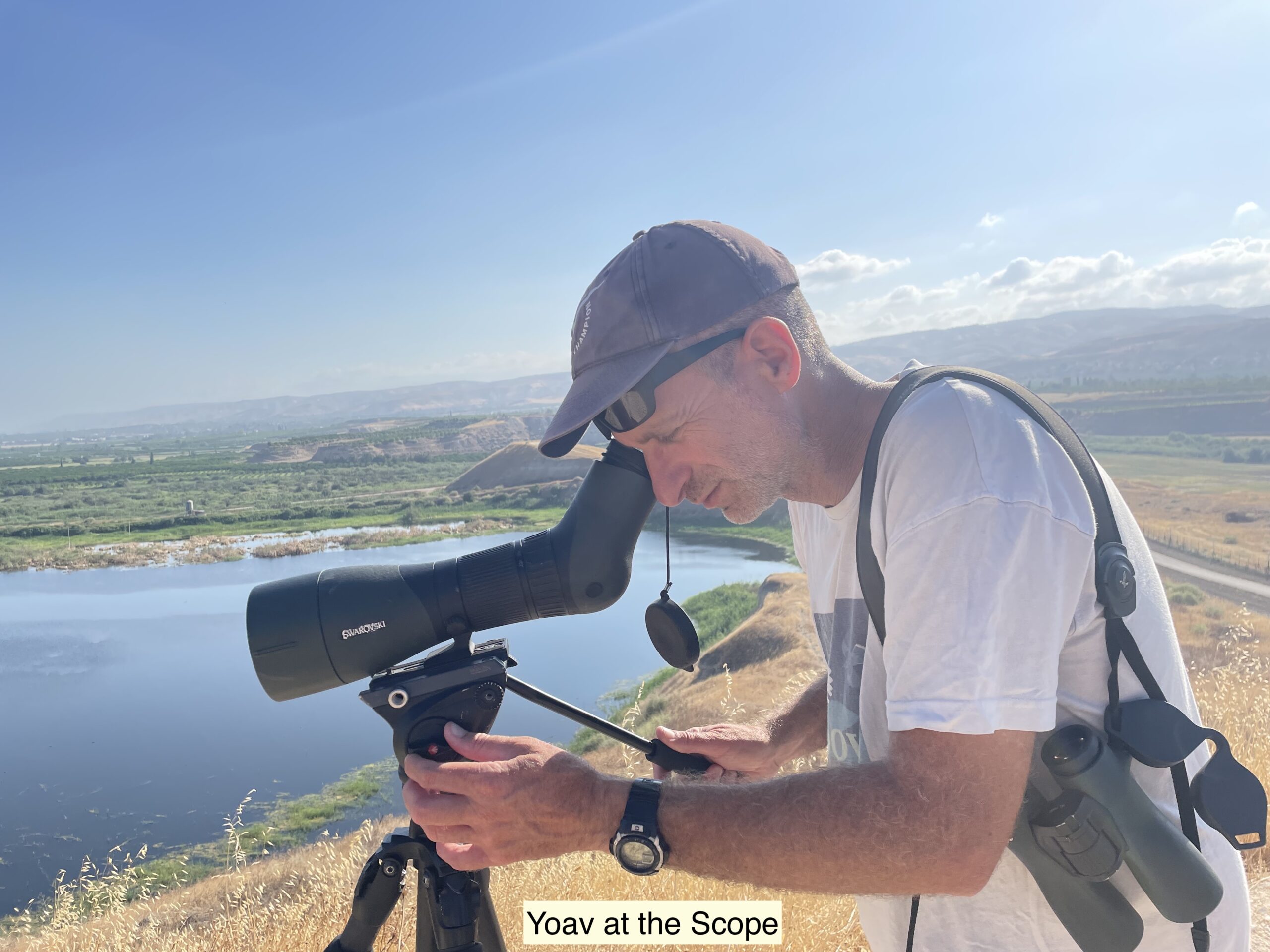

Yoav jumped to the trunk and set up his birding scope. In an instant it was focused on the reservoir down the road.

“There must be thousands of birds here!” Yoav said, focusing the knob.

Between exclamations that would require a sudden reorientation of the scope— “Arabian green bee-eater!”—and taking turns at the eyepiece, Yoav described to us the history of the site.

By the 1950s (and a bit earlier or later depending on the exact location), 95% of Israel’s wetlands were drained for agricultural land or turned into fishponds, becoming the primary revenue sources for many kibbutzim. Since 500 million birds migrate over Israel twice a year, this land transformation was devastating. Still, many birds adapted: if a wetland was like a deluxe supermarket, then a fishpond was like an aging gas station convenience store.

Life limped forward.

Then about 10 years ago, Israel and China struck a new trade deal, making fish importation incredibly economical. The fish-farming industry within Israel collapsed virtually overnight, and, along with it, the livelihood of many kibbutzim. The birds were in their gravest situation yet, since their gas stations were now being drained and deserted, or otherwise altered. Soon, the birds would have nowhere to stop.

Like other kibbutzim, Kfar Ruppin tried growing wheat after the trade deal—Yoav pointed out one of these failed projects—but the land after decades of holding water rich in organic matter was simply too marshy. Like the birds, Kfar Ruppin was in danger of losing everything. In need of a new source of revenue, SPNI offered a creative solution.

“It’s not only a financial deal. It really is a partnership with the kibbutz,” Yoav explained. SPNI had gained responsibility over two fishponds via long-term leases with Kfar Ruppin, restoring the spots into healthy, biodiverse wetland systems. We were looking at the Amud Reservoir, the champion of Start-Up Nature. It was the third summer of managing the reservoir, and the primary objective had already been achieved: we saw a breeding pair of Ferruginous ducks, a globally threatened bird with a rich brown coat.

“We did this for them,” said Yoav. “This was to be a sign of success. And here they are.”

His face glowed with pride. It really was a remarkable turn of events: the land had been restored, and nature had responded with an emphatic, “yes.” From above, a natural spring delivered water through beds of reeds and curves, coming into the reservoir in a slow, sweet trickle. There were tens and tens of endemic aquatic plants, providing shelter and nourishment. Submerged vegetation stuck out of the low water levels—exactly how it was supposed to be: summer heat evaporated the water, revealing lots of mud. “Birds love mud,” Yoav explained.

The place was ripe with life. We had watched two European bee-eaters share breakfast on the telephone line— “It’s just the most beautiful bird, like a rainbow of a bird,” said Yoav—saw a Kingfisher swoop in, and marveled at a group of Common terns glide across the water like white angels over black glass. Among that scene, it was easy to see how one fell in love with the place, and why the kibbutz delighted in it:

“It’s not just [a way] to make money,” said Yoav. “It’s a way of life.”

The birds and the kibbutz were back in the game.

If you would also like to live and breathe these places fully, I encourage you to check out Nature Israel’s upcoming November trip, which you can find here.

Meanwhile, I’m thrilled to be on this adventure, and for you to be joining me!